- Home

- Fundamentals of Drawing

- Thumbnail sketches

What Is a Thumbnail Sketch? A Quick Guide with Examples

One common question I get asked as an artist is 'What is a thumbnail sketch?"

Simply put, it's a small, rapid sketch that helps me visualise the composition of a larger piece.

I create these 2 x 3 inch sketches to get a feel for the overall arrangement of elements before committing to a bigger project.

Thumbnail sketches are quick, rough, and often done in graphite or charcoal pencil on small pieces paper. They're not meant to be finished artworks, but rather a starting point to explore the composition, placement of subjects, and background. If a sketch shows promise, I'll progress to a full-size drawing in graphite or colored pencils.

The process can be iterative, requiring multiple thumbnail sketches until I'm satisfied with the arrangement.

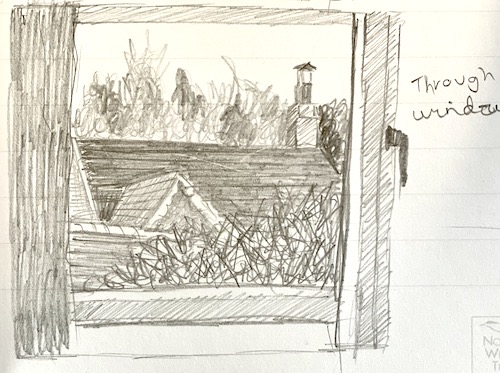

The example above illustrates the purpose of a thumbnail sketch.

It's not a polished drawing, but it helped me decide whether to include a window frame to "frame" the view. After 15 minutes of sketching, I achieved my goal without wasting time or materials, and I could move on to explore other ideas.

By using thumbnail sketches, I can efficiently experiment with different compositions, saving time and energy in the long run.

This technique allows me to focus on the essence of the artwork, ensuring a stronger final piece.

Rearranging the landscape in a thumbnail sketch

When planning a landscape in colored pencil, I experiment with different compositions by moving elements around in my thumbnails. A tall tree on the right in real life might look better near the middle or on the left in my drawing.

I start by placing the horizon line, deciding whether to emphasize the sky or the foreground. I often create thumbnail drawings for both options to see which I prefer.

Achieving balance is crucial, and I avoid crowding elements into one area. This is where drawing has an advantage over photography – I can reposition elements to create a more harmonious composition.

Trying to create a balance in my sketch without crowding everything into one area is important. This is one of the benefits of drawing over photography; just because a tree seeded itself in one position doesn't mean that is where it belongs in my artwork.

Indeed, thoughtfully placing (or repositioning) key elements like trees is vital for a harmonious outcome.

For a real-world example of an artist navigating these very decisions in a landscape, the resulting impact on compositional balance, and the important lessons learned, you might find our process study insightful: Lessons in Landscape: A Watercolour Pencil Background and Composition Study.

Sketching from different angles can be helpful, even if none of the individual sketches feel quite right. By combining elements from multiple sketches, I can create something better than each one on its own.

Thumbnails aren't about precise shapes or details; they're about capturing the essence of an element.

A long, thick line might indicate a tall tree, a rough rectangle a building, and a scribble a bush or hedge. These sketches aren't for transferring outlines to my drawing paper, but for exploring ideas and arrangements.

My thumbnails are private, a messy but essential part of my creative process. I rarely share them, but this page shares a rare glimpse into my sketchbook.

What is a thumbnail sketch for? - Balancing values

In art, values refer to the range of values from dark to light. Achieving a harmonious balance between these tones is crucial for a visually appealing image. To get it right, I rely on thumbnail sketches – a quick and effective way to experiment with different balances of light and dark.

Using a black marker, I block in the darkest areas, leaving the lightest areas as the white of the paper. This simple technique helps me visualize which coloured pencils I will use later to ensure a balanced composition. I might add a dark foreground element, like a river's edge, or extend a line of trees to create a dramatic background.

The area with the greatest contrast will naturally draw the viewer's eye, becoming the focal point. By creating thumbnail sketches, I can test and refine my composition, achieving a harmonious balance of values that guides the viewer's gaze.

Adjusting Lighting in a Thumbnail Sketch

In addition to rearranging elements, I can also experiment with different lighting setups in my thumbnail sketch.

If my reference photo was taken at a different time of day than the scene I want to depict, I may need to reposition shadows and highlights.

For example, I might want to shift the shadows to a different wall of a farmhouse.

By testing this in my thumbnail, I can make notes and mark the ideal sun position with a symbol, refining my composition before moving forward.

Capturing Perspective with Thumbnail Sketches

Achieving accurate perspective in a scene can be challenging. To overcome this, I sketch the horizon, eye level, and vanishing point of a perspective line in my thumbnail sketch.

This simple step helps me create a drawing with depth, rather than one that looks flat and unconvincing.

When working on location, a thumbnail sketch serves as a valuable guide for the final piece. I use it to experiment with different viewpoints, often walking around to find the most compelling angle.

This process can reveal new and interesting elements, which I might incorporate into my final drawing.

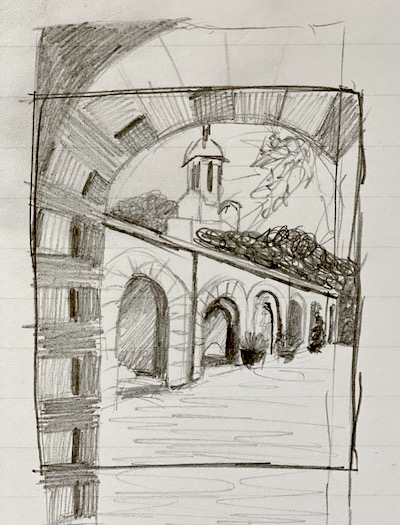

The thumbnail sketch above illustrates this process.

I stood under an arch to frame the view of the stables, adjusting the composition as I worked. I balanced the dark values of the arch with the trees and shadows behind the building, creating a sense of harmony.

This exercise also shows that I don't worry about erasing mistakes – the goal is to explore ideas, not create a perfect drawing.

Thumbnail sketches can benefit artists who work from imagination or create abstract art.

Starting with a small sketch can help develop design ideas and ensure a strong foundation for the final piece.

While I prefer to work from reference, I often transform the original image beyond recognition, demonstrating the flexibility and creative potential of thumbnail sketches.

The Time it Takes to Create a Thumbnail Sketch

A thumbnail sketch typically takes me around 10-15 minutes to complete. I stop once I've extracted the information I need, even if it's not polished.

If a sketch isn't working, I discard it and start anew.

The goal of a thumbnail sketch is to serve as a preparatory drawing for the final artwork, not a standalone project.